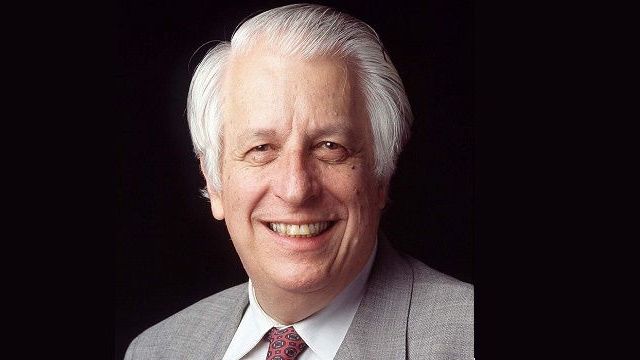

Eminent Australian scientist Sir Gustav Nossal has revealed his family story of dementia, calling for more research into the disease affecting 459,000 Australians.

The 89-year-old renowned immunologist and former Australian of the Year for his research in Australia and internationally told Swinburne University of Technology’s Barbara Dicker Oration 2020 his wife of six decades, Lady Lyn Nossal, developed symptoms about five years ago.

“The first few things were very subtle,” he said.

“She found it difficult to manipulate the automatic teller machine at the bank. She found it difficult to give the correct change or to figure out you know small amounts of money as she was doing shopping.

“Then gradually over a period of probably about five years her function in all respects began to deteriorate, both language and even mobility.”

This year’s Barbara Dicker Oration focused on tech-enabled innovations to assist and care for people living with dementia, the people who care for them, and healthcare workers.

A panel discussed the social impacts of the disease as well as the technology-driven interventions available to help people living with dementia.

Sir Gustav said his wife and best friend had been living in residential aged care since her movement became “frozen”.

“It’s difficult to know what’s going on in her mind,” he said. “I think she still recognises me, she certainly recognizes that it’s someone that’s a positive influence.

“I think the biggest challenge by far has been to accommodate to the fact that this person – the closest thing to you in the whole world and who you know you’ve known for 60 years as dynamic, intelligent, very vigorous, very positive type of person – all of a sudden is becoming passive.”

“She accepts it quite modestly and humbly.”

Since the COVID-19 pandemic he had continued to visit daily, smiling and gesturing through a glass wall.

“It’s a funny sort of communication but I’ll tell you what, it is quite real. I don’t do it out of a sense of duty I do it because I want to do it,” he said.

“It maintains that connection.”

He called for more medical research into dementia and its causes, even if it is “enormously difficult”. “We’ve got to try,” he said.

Work is underway in both the media research and for interventions to assist people living with the condition.

Professor Nilmini Wickramashinge, Deputy Director Iverson Health Innovation Research Institute at Swinburne uses artificial intelligence to identify symptom clusters in people.

In the “digital twin” project, data analysis will then try and predict the trajectory of the disease and intervene in those changes.

“The idea is to try and develop the most personalised support for each individual that has dementia,” she said.

“The idea there therefore is once you can identify the trajectory you can then …. tailor the mobile solutions to facilitate the monitoring.”

Professor Jane Farmer, Foundation Director Social Innovation Research Institute at Swinburne highlighted the impact on regional and rural people with dementia, given services are spread out.

She said access to specialists and clinics through telehealth could assist regional people.

“It’s important to think about tele health as being a way for rural practitioners to to have access to training and to have access to a wider kind of community of practice

“It’s about thinking about the everyday with dementia and that people are more than their diagnosis and putting ourselves in in the shoes of people with dementia and their families and carers

“Technology can’t be a solution on its own but it can be really helpful in the lives of people with dementia in terms of things like monitoring and alarm systems and basic help.

Co-director of the Wellbeing Clinic for Older Adults at Swinburne Professor Sunil Bhar established telehealth psychology clinics in residential aged care during the COVID-19 health.

He said Dementia Australia had developed a virtual reality training program for healthcare workers to immerse them in the experience of a person with dementia.

The VR simply follows the progress of a person with cognitive difficulties as they negotiate their way from their bedroom to their bathroom.

“What better way to instill a sense of empathy if not by giving the individual a first person’s point of view,” he said.

He said more translational research was needed to apply the learnings from the clinics into the wider aged care sector.

Excellent article IA and thanks for sharing. In our latest episode of the Aged Care Enrichment Podcast, we spoke to Stephanie Bendixsen (a TV presenter and author who has worked extensively in video games and technology and an Ambassador for Dementia Australia.)

Stephanie lost her mom to Alzheimer’s in 2018. Since then she has been sharing her experiences with the disease in the hope of helping people be more prepared to face it than she and her family were.

It’s a conversation where you will hear some very honest truths as Stephanie digs into what she wishes she has done differently in her mom’s final years and what resources are now available to make life easier for people living with dementia.

Your readers who find this article interesting, may very well enjoy a listen. The episode can be found on all major podcasts like Apple, Spotify, Google etc. by searching “Aged Care Enrichment” or following this link:

https://ace-aged-care-enrichm.captivate.fm/episode/ep-06-stephanie-bendixsen-accepting-dementia

[…] particularly unusual due to her young age, in terms of dementia diagnosis. Dementia is the second leading cause of death of Australians and in 2016, became the leading cause of death of Australian women, surpassing heart […]